Heading west to Normandy for our WWII D-day trip with Paul Woodadge (ddayhistorian.com) meant dealing with a Parisian train station (Paris Gare St. Lazare), with which we were not familiar. Previously, we had been traveling south to Beaune or Provence or Switzerland from the familiar Paris Gare Lyon and had been issued tickets that required no stamping at the small yellow punch-in machines. All that was required was keeping an eye on the departure board to get our track number. At Gare Lyon, you want to get an advance beat on where each of the three departure options is located. Be warned, though, train travel with mega luggage is at your peril. It can be no easy task boarding, moving about the train, and offloading if you are loaded down with jumbo bags. We travel with two carry ons each, which allow us to move through airports (no checked luggage) and train stations with vigor.

Our first-time trip out of Paris Gare St. Lazare with only our E-ticket RAILEUROPE printouts in hand meant an encounter with the rail station ticket machine and a confirmation punch at the little yellow trackside machines. Well, the printout machine (easily located in the station) advises you to input your e-ticket number for printout. No problem-o, right? No indeed. I expertly punched in the TGV 4-digit number, which promptly registered a distress sign. Try again. No go. Now, with some concern, I must track down a ticket agent and use my far-from-fluent bistro French. Well, I find the office, lineup, and roll out my best Bonjour monsieur, parlez- vous anglais, to be answered in perfect English, how can I help you, sir. My problem was that I needed to enter a six-letter code, rather than the numbers indicated on my RAILEUROPE instructions. There it was—e-TMICCR. I was in business and moved fast back to the ticket printout machine. In went e-TMICCR and my last name and, bingo, out came my ticket. Made the same deft move for Deb, scanned the departure board for our track number, which turned out to be an 8-iron shot up the station floor and we were moving.

Around us, it looked like a migration of NFL-sized equipment bags being dragged along by folk the size of Sesame Street characters. What a horror for all those folk. We were able to move rapidly out, stamp our new tickets at the little yellow machines, and clamber on board sans further to-do. It helps to check the electronic train configuration board, which conveniently displays the numbering order of the train cars. Trust me, you want no part of hurdling steamer trunks in the scant few minutes you are given to board the train before it promptly hisses onward. In advance, know where on the station platform to stand. Your track may require a flight of stairs, so get to the station in time to scope out the scene. And of course, do not forget to stamp your return ticket at the little yellow machines.

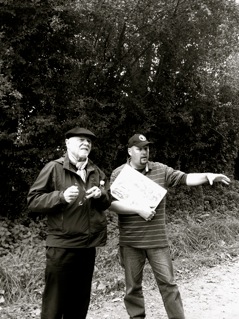

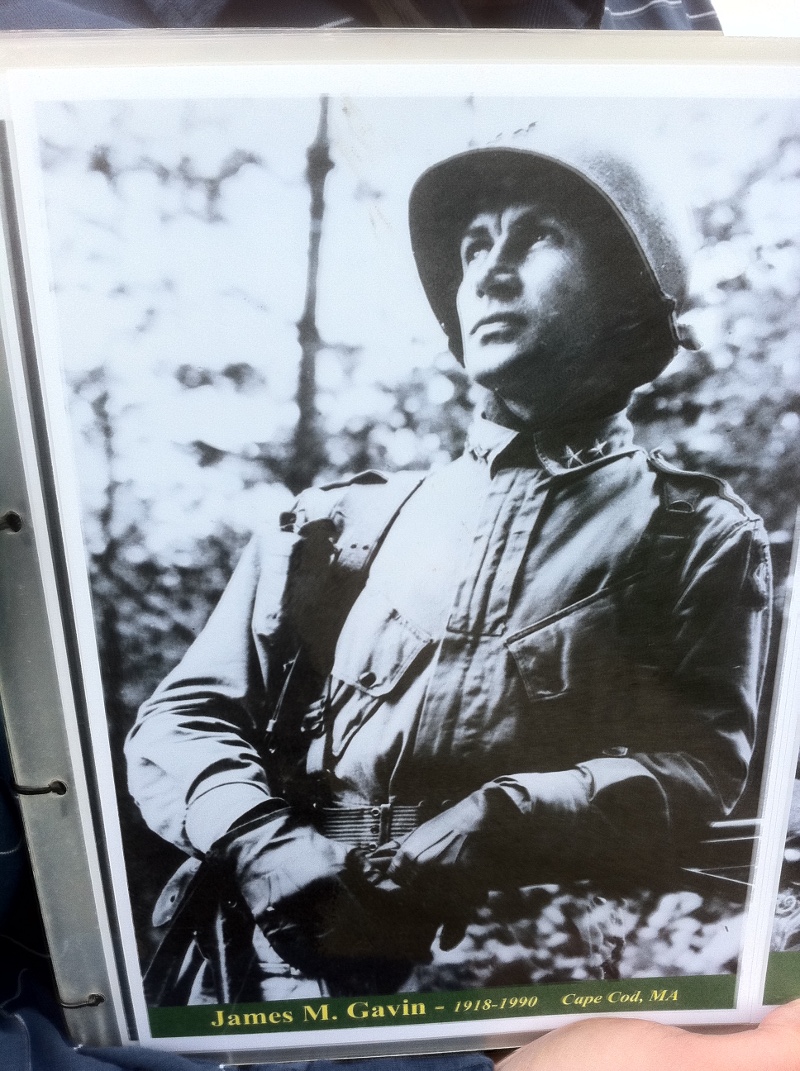

In  Normandy, we were met by our drill-sergeant-oriented historian (meant as a compliment). Off we were with Paul Woodadge to the Merderet River crossing, the scene of one the most strategic ground battles of the Normandy invasion. The landscape at the Normandy Bridge has changed little since the 82nd Airborne Division, under the command of General James M. Gavin, defeated the dug in Germans in June of 1944. Gavin’s paratroopers had flown in through a dense cloudbank and in dangerously close formation. Antiaircraft gun positions threw heavy flak to the right of the formation. At only 600 feet, the green jump light came on and the “let’s go” signal was given. In moonlight, a wide river could be seen below. Days of fighting in between the Merderet and Douve rivers were difficult due, in part, to the preponderance of thick hedgerows. A superior Allied navy and air force, along with the “new weapon”—the airborne troops—ultimately won the day, however, for the Americans and Brits against the Germans, despite the Germans’ strong fortifications.

Normandy, we were met by our drill-sergeant-oriented historian (meant as a compliment). Off we were with Paul Woodadge to the Merderet River crossing, the scene of one the most strategic ground battles of the Normandy invasion. The landscape at the Normandy Bridge has changed little since the 82nd Airborne Division, under the command of General James M. Gavin, defeated the dug in Germans in June of 1944. Gavin’s paratroopers had flown in through a dense cloudbank and in dangerously close formation. Antiaircraft gun positions threw heavy flak to the right of the formation. At only 600 feet, the green jump light came on and the “let’s go” signal was given. In moonlight, a wide river could be seen below. Days of fighting in between the Merderet and Douve rivers were difficult due, in part, to the preponderance of thick hedgerows. A superior Allied navy and air force, along with the “new weapon”—the airborne troops—ultimately won the day, however, for the Americans and Brits against the Germans, despite the Germans’ strong fortifications.

The Le Merderet Bridge was the scene of a bloody and crucial turning point for the Allies in the war. It would later inspire the climactic battle in the film Saving Private Ryan.

Thanks to Paul, Debbie and I were able to track the very course General Gavin’s paratroopers had taken in the early summer of 1944. And it was easy to imagine the din of the incoming 82nd airborne troop carriers. Standing at the innocuous little bridge along the Merderet, Paul dramatically explained how a lightly armored French built tank had been knocked out by a close-at-hand American grenade lob. The disabled tank on the causeway at the head of the bridge made logistics tough for the Germans by preventing two support tanks and German ground forces from crossing. As I write, I am checking facts in my brother’s personally signed copy of Jim Gavin’s On to Berlin. Our dedicated historian/guide Paul was pretty shocked that I had actually met General Gavin. My dad had worked with Gavin at industrial research firm Arthur D. Little in the mid sixties. The general was then chairman of the board.

Living WWII history is what our trip to Normandy turned out to be. I will have more for you in coming weeks and will be able to explain to you more of the neat stuff Paul Woodadge related to us, including Paul’s first-hand friendship with many of the D-Day soldiers, including Sergeant William Guarnere, portrayed so splendidly in The Band of Brothers mini-series. Debbie and I both read and watched Band of Brothers before our Normandy trip with Paul. Watching the series, hearing Paul’s detailed stories, and seeing his personal photo albums of the guys he had become close to later in their lives made us feel as though we knew many of the soldiers personally. Even though we were well prepared to find a visit to Normandy moving, we were still staggered by all we learned from Paul on our trip and how much there is still to learn. I hope I have provided you with even a small shred of the emotional story of Normandy and the D-Day invasion.

Warm Regards,

Dick

Reposted from Friday, October 21st, 2011.

If you’re willing to fight for Main Street America, click here to sign up for my free weekly email.