You don’t need a report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to tell you food and energy prices are up. Economists like to strip them out of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to reduce comparison volatility. It would be nice if we could do the same when it comes time to pay the bills. But for you and me, it seems the only direction is up.

One of the most destructive forces affecting your ability to pay for anything is Washington’s weak dollar policy. The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices. The two end up being opposing forces. Clearly, higher unemployment is deflationary while a weaker dollar is inflationary.

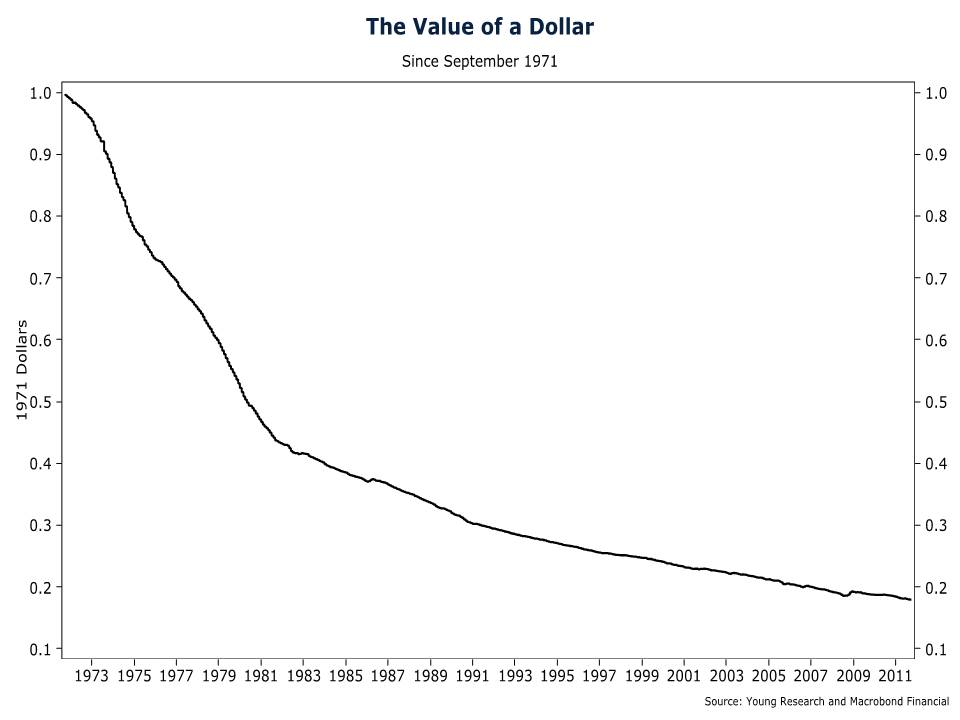

To help maximize employment, the Fed gave us two rounds of quantitative easing and Operation Twist. From a stable prices standpoint, inflation has eaten away at the purchasing power of the dollar. The purchasing power of a dollar has fallen by 80% since 1971.

Fed policy is the most destructive retirement reform, and it’s going on before our very eyes. It will destroy the purchasing power of those on a fixed income, whether it’s a pension or a private account. In September, the CPI was up 3.9% versus a year ago. It’s increased at a 4.8% annual rate in the past three months. You cannot print dollars out of thin air without inflation.

States Can’t Print Money

The difference between state debt and government debt is that states can’t print money when they’re in trouble. They use other tools. This year, Rhode Island’s Governor Chafee passed legislation to help municipal bond investors.

The law requires municipalities to guarantee lenders the first right to property taxes and general revenues in the event of bankruptcy. When Central Falls filed for bankruptcy a month or so later, its muni bond prices barely budged.

Moody’s has maintained darn good ratings for a number of Rhode Island towns and cities. Muni bond prices have been strong. But legislation protecting investors can only go so far. First dibs on revenues aren’t much of a help when there are no revenues. The muni bond legislation has lulled Moody’s to sleep. Pension reform is attempting to do the same thing. Let’s not forget that it was the same ratings agencies that completely missed the real-estate crash.

Good News from Central Falls

If there’s anything good to take away from the bankruptcy of Central Falls, it’s the advances in transparency. Who would have thought taxpayers were picking up the racing entry fees for a disabled retiree, who happens to be winning his division on the taxpayer tab?

Government reports are usually about as transparent as waxed paper over your windshield. Now that Judge Flanders is picking apart the finances, we see that for the 10 years from 1978 to 1988, 92% of the police officers and firefighters who retired did so on accidental disability. All but 3 of the 36 retired from the city with on-the-job injuries, half of them pegged to stress or hypertension. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. Judge Flanders refers to the unfolding situation in Central Falls as “scam heaven.”

Stock-Market Losses

General Treasurer Gina Raimondo’s pension reform is troubling. The state’s most recent five-year average return is only 1.52%. She hasn’t been educating Rhode Islanders or getting out in front of this problem like she should be. It’s like she’s hoping it will simply go away.

That’s hoping for a lot. When reviewing pension performance, it’s important to remember the accounting method used for gains and losses. It’s called “smoothing”—taking an average of the last five years. This means the state will be paying for the 2008 stock-market losses until 2013. In 2008, the S&P 500 was down 37%.

One way to think about the problem is that every year starts with a loss of 7.5%, or the expected return. Subtract from that any losses incurred in prior years and then add gains, if there are any. Through the first three months of this fiscal year, the plan is down over 8%. That’s a lot of ground to make-up, especially considering the plan is invested like a balanced fund.