Earlier this year, the House Budget Committee advanced the Fiscal Commission Act of 2024. Cato Institute’s Romina Boccia explained the purpose and function of the commission as similar to the Base Realignment and Closure process (BRAC). She wrote on Downsizinggovernment.org:

Key Features of a BRAC‐Like Fiscal Commission

- Clear Objectives: The commission is tasked with generating policy proposals that would stabilize the debt at 100 percent of GDP within 10–15 years. Changes to programs governed by trust funds should improve 75‐year solvency.

- Independent Experts: All commissioners are independent experts nominated by Congress and/or the president, and confirmed by the Senate.

- Public Accountability: In a departure from the original BRAC commission, the commission would publish meeting agendas and minutes, provide public access to documents and data used in its work, and hold public hearings and community forums for public input. The commission would publish periodic reports on its findings and deliberations. Such transparency is important due to the wide‐ranging reforms being considered.

- Certified Results: Oversight agencies, such as the Congressional Budget Office, the Government Accountability Office, and the Social Security and Medicare Trustees certify that a reform package achieves debt stabilization and that any changes to trust fund programs improve 75‐year solvency.

- Fast‐Tracked Authority: The president reviews the commission’s recommendations. If approved, they are sent to Congress as a comprehensive package. If rejected, the president provides detailed objections, allowing the commission to revise its recommendations.

- Silent Approval: Upon presidential approval, the commission’s recommendations become self‐executing after forty‐five days. Congress has the option to pass a joint resolution rejecting the reform package using expedited procedures.

Key Differences: BRAC‐like Fiscal Commission vs. Fiscal Commission Act of 2024

- Commissioners: The Fiscal Commission Act relies primarily on legislators as commissioners, including experts only in a non‐voting, advisory capacity. A BRAC‐like commission is either composed entirely or primarily of independent experts, enabling a more objective assessment of policy solutions.

- Approval: The BRAC‐like commission uses silent approval, avoiding the need for an affirmative vote in Congress. The Fiscal Commission Act requires members to vote on the commission proposal before it can go into effect. While expedited procedures will help, such a vote will be politically risky and could undermine the commission’s success.

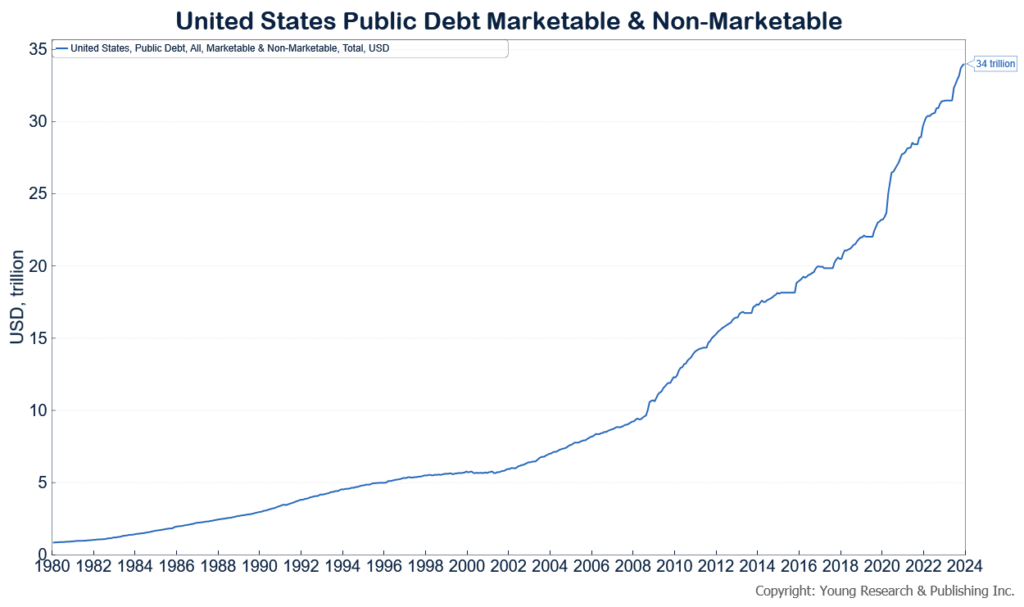

There is no question America’s debt is a problem. Look at the chart below showing America’s debt, which has grown to over $34 trillion.

After the Act’s passage through committee, it has come under heavy fire from the defenders of big government. Boccia deftly takes their arguments against the creation of a fiscal commission and debunks them at Cato.org, writing:

Below I list prominent critiques and their main charges, and defuse each argument in turn:

Claim: “Social Security and Medicare Part A are fully self‐funded and do not contribute to the debt…(National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare); “Social Security and Medicare “should be protected in any discussion about the debt or deficit…Social Security is not a driver of the nation’s debt, so it shouldn’t be cut to pay it off.” (AARP)

Response:

Social Security and Medicare are major contributors to the US budget deficit (making up 11 and 33 percent of the 2023 deficit, respectively) and national debt, with no real assets to back up their promises. Both old‐age benefit programs face a huge funding gap that will require either benefit cuts or tax hikes in the near future. These programs are financially unsustainable and require reform to avoid indiscriminate benefit cuts by 2031 for Medicare and by 2033 for Social Security. You can find more details about the dire financial situation of these programs here.

Claim: “Any changes to Social Security and Medicare should go through regular order and not be relegated to a commission unaccountable to the public and rushed through the Congress.” (National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare)

Response:

The 16‐member fiscal commission consists of 12 elected officials who are accountable to the public, and only elected officials are eligible to vote on the commission. The commission’s proposal would benefit from expedited procedures in Congress but would still need to be voted on by both the House and Senate, including clearing the 60‐vote Senate threshold, plus clearing the president’s desk as a final step. Hardly an unaccountable process. Moreover, the federal budget process is broken, and Congress rarely follows regular order. In the 49 years since the budget process was established, Congress followed regular order only four times. In 17 of these 49 years, Congress avoided passing any budget, period. You can find more details about the fiscal commissions’ design and limited powers here.

Claim: The biggest drivers of the debt are ‘tax expenditures’ – giveaways to the wealthy and large corporations like the Trump/GOP tax cuts of 2017 that Republicans insist be extended.” (National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare)

Response:

Spending increased 42 percent, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) between the peak budget surplus in 2000 and 2022. Revenues declined by a measly 2 percent over that same period. Clearly, the growth in spending is the biggest driver of US debt. My colleague Adam Michel gave congressional testimony on this very topic. He wrote:

“Current data show that if the Treasury collected as much revenue [today] as it did in 2000 when it had a 2.3 percent budget surplus, it would still have a budget deficit of about 5.1 percent of GDP [today]. Between 2000 and 2022, total federal outlays as a percent of GDP increased by 7.4 percentage points, from 17.7 percent to 25.1 percent, according to Office of Management and Budget data. Figure 4 shows that total receipts fell by 0.4 percentage points during the same period, from 20.0 percent to 19.6 percent. In 2000, the federal government had a budget surplus of 2.3 percent of GDP; by 2022, the surplus had turned into a deficit of 5.5 percent of GDP.”

Read more of her responses here.

If you’re willing to fight for Main Street America, click here to sign up for the Richardcyoung.com free weekly email.