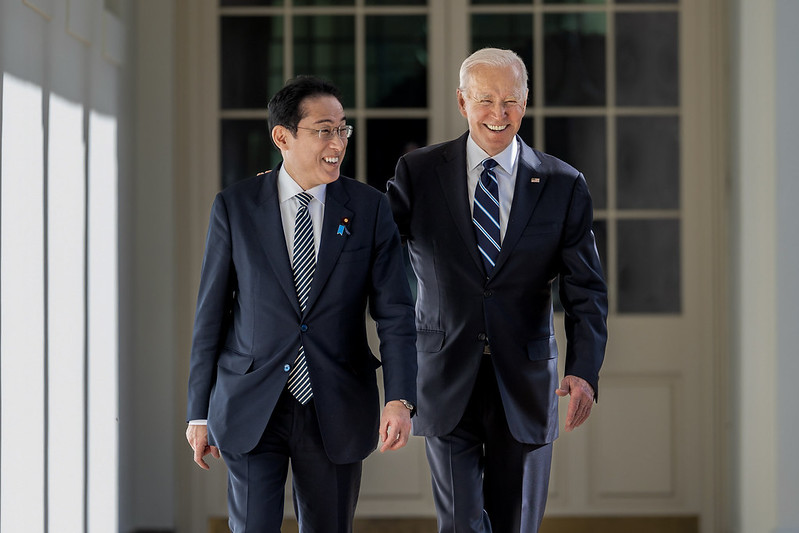

President Joe Biden walks along the West Colonnade with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, Friday, January 13, 2023, at the White House. (Official White House Photo by Cameron Smith)

In Spectator World, Jason Morgan, an associate professor at Reitaku University in Kashiwa, Japan, discusses the move by Japan to bulk up its military and strengthen the bond between itself and the United States. He writes, skeptically, of the move:

In December 2022, for example, the Japanese prime minister, Kishida Fumio, announced plans for a budget that will bring military spending up to 2 percent of GDP by 2027. This is historic. It marks a more than 50 percent increase over present figures, and a doubling of the 1 percent of GDP benchmark that has been almost an article of political-religious faith during the postwar period.

The huge spending increase, coupled with the release of three major security-related documents adding institutional heft to Japan’s upgrades in military hardware, represent a turning point. Japan’s wimpy postwar era is over. This East Asian archipelago is making a big play to match its economic might with formidable firepower, something the Japanese establishment has been reluctant to do since the closing months of 1945.

The ripples in East Asian and world politics from this move will be big and disruptive — and much for the better, in my view. Japan sits cheek-to-jowl with Russia, North Korea and the People’s Republic of China, all of which could use a whiff of grapeshot now and then.

Yet the Japanese media, and many politicians, are curiously uncurious about the way the world through which those ripples will propagate works. There are endless Japanese shows and newspaper articles about foreign countries, to be sure. Analysts pontificate from television studios and in print about foreign policy, foreign leaders, foreign trade. Politicians often appear on these shows too. There appears to be a healthy debate going.

But there is almost nothing beyond the standard Washington narrative when it comes to the realities driving geopolitics. Sticking by the Americans’ side is a given, almost a weird patriotic duty. “Global,” in Japan, is virtually a synonym for “whatever Washington wants us to do.”

This is even truer when it comes to knowledge of Washington itself. I have found many in Japan who think Washington is a corrupt and self-serving cesspool and that Japan has no business blindly following orders from Uncle Sam. But when it comes to establishment types in Tokyo, such entreaties fall on deaf ears. Freedom, democracy, human rights — these slogans are repeated ad nauseam, with no apparent interest in whether the US-Japan alliance enhances or trammels them.

***

One indication of how deeply dependent Tokyo is on Washington occurred back in January.

The Japanese center-right has been pushing for a beefier US-Japan alliance for decades, arguing that the postwar Japanese constitution, which emasculated Japan and made it dependent on Washington, should be scrapped.

But when the time came to do it, Tokyo balked. Shinzo Abe, the transformative prime minister who was slain in the ancient capital of Nara last July, spent his entire balance of political capital trying to get Japan to stand on her own two feet. He wanted Tokyo to play a leading role in Asia, not eternal Robin to Washington’s Batman.

One of Abe’s successors, Prime Minister Kishida, however, cashed in that capital for an even closer embrace of Tokyo’s Washington master.

On January 13, Prime Minister Kishida, wrapping up a tour of the G7 countries, sat in the White House with Joe Biden, chatting about the Japanese-American friendship. During his trip, Kishida had played up Japan’s new abilities to launch counter-strikes against enemy bases and the general toughening of Japan’s military strength. Kishida, however, framed it as helping to shore up the deterrence (yokushiryoku) and response (taishoryoku) capabilities of, not Japan, but the US-Japan alliance.

Read more here.

If you’re willing to fight for Main Street America, click here to sign up for the Richardcyoung.com free weekly email.