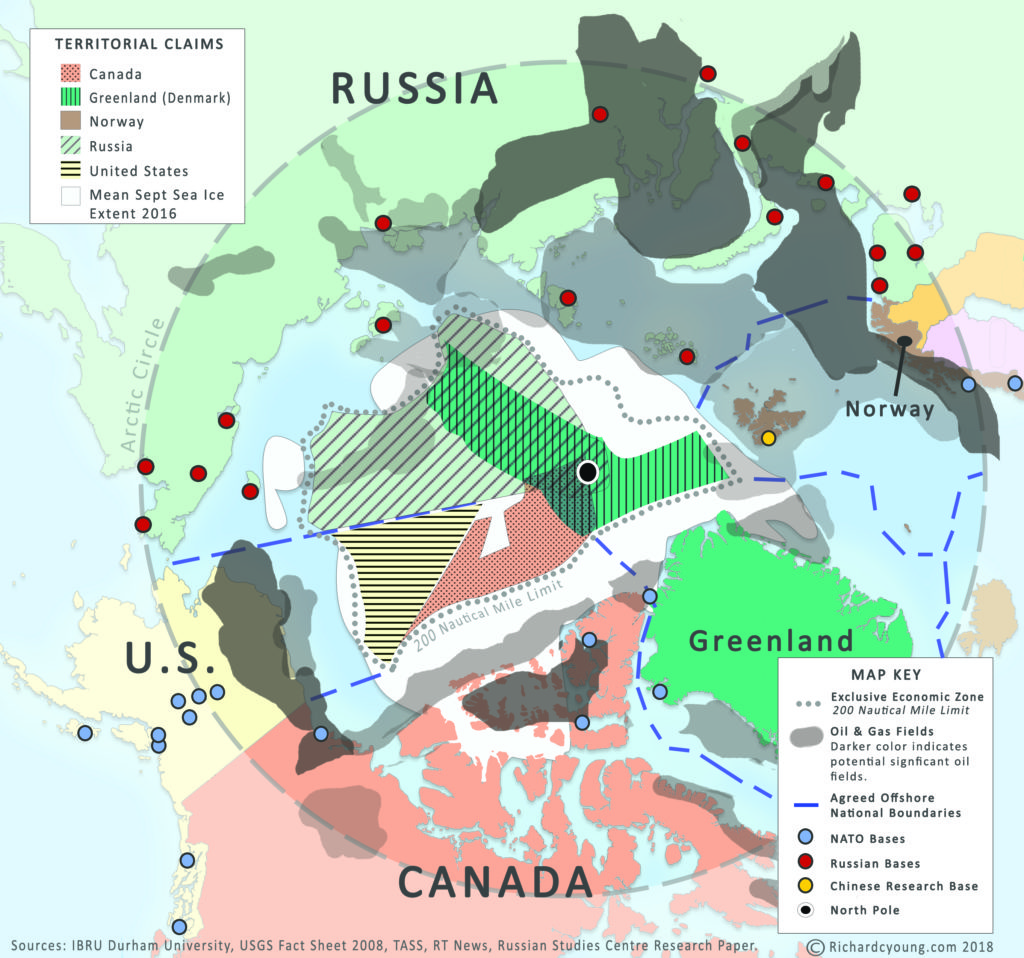

The Arctic region holds an estimated 90 billion barrels of oil and about 30% of the world’s undiscovered natural gas. It is also of immense strategic importance for global trade and national security. Many countries have laid claim to parts of the Arctic. Russia in particular is pumping major resources into its northern defense, so much so its neighbors are alarmed reports Paula J. Dobriansky of the WSJ.

In recent years the Arctic has seen a massive Russian military buildup including the addition of a new Arctic command, four new combat brigades, 13 new airfields protected by S-400 long-range surface to air missiles, 16 deep water ports, and a fleet of 40 ice breakers, with 11 new ones on the way. Russia has also ordered two icebreaking corvettes specifically designed to carry its latest anti-ship missiles.

Dobriansky writes:

The Arctic is a region of tremendous strategic importance for global trade and national security. The High North is also experiencing a massive Russian military buildup, which calls for the U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization to adopt a new strategy.

Vladimir Putin has been hyping the threat posed by U.S. attack submarines deployed in the Arctic Ocean. Meantime, Russia has been using Arctic waters as a sanctuary for its ballistic-missile-carrying submarines—the key component of its strategic nuclear forces—and wants to enhance its regional military infrastructure to protect them. This is driven by Moscow’s longstanding view that a nuclear war can be won by a better-prepared side.

With these strategic imperatives in mind, Russia created an Arctic Command, which became operational in 2015. It has also embarked on a costly military buildup—new airfields, ports, air-defense installations and barracks—and heightened the tempo of military exercises and activities.

Moscow’s Security Council has designated the Arctic as a “main strategic resource base.” The Council on Foreign Relations reported in 2017 that products from the Arctic account for 20% of Russia’s gross domestic product and 22% of its exports. Much of this is energy—95% of Russia’s natural gas and 75% of its oil.

The United States faces an uphill climb as it finds itself behind militarily and commercially in a region that holds such strategic importance. To make matters worse, its main base in Northwestern Greenland could face some uncertainty this month. Thule Air Base is America’s most northerly base, just 1000 miles from the North Pole. It holds vital radar installations that make up an important early warning node for the U.S. missile defense system. Heather Conley of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) talks about how Greenland’s April 24th snap election could potentially be an issue for U.S. Arctic defense.

Conley writes:

Climate scientists have been surprised by the sudden and unusual rise of Arctic temperatures this winter. Arctic political watchers were equally taken by surprise this week when, on March 5, Greenlandic premier Kim Kielsen called a snap election to be held on April 24. Surprising Greenlanders and even members of parliament from Kielsen’s own party, what was his motivation and why now?

Why is this election important to the United States? Because Greenland plays a vital role in U.S. defense. The Thule Air Base in Northwestern Greenland, less than 1,000 miles from the North Pole, is the United States’ most northern base, and its radar installations make up an important early warning node for the U.S. missile defense system. Greenland-based airports and ports can become crucial support points for maritime and air patrols in the North Atlantic, while underwater submarine detection systems can be placed along the coast.[…]

According to the Economic Council of Greenland, Greenland’s economy will become steadily more unbalanced in coming decades with annual budget deficits of more than 5 percent of GDP even with support from Denmark. Therefore, although independence from Denmark is popular with most of Greenland’s 58,000 inhabitants (88 percent have either an Inuit or mixed Inuit background, 12 percent of the population are Danes or other Europeans) and is favored by all parties in the 31-seat parliament, the economic numbers simply do not add up to allow for independence in the short to medium term. But the numbers may begin to change. As with so many others, the Greenlandic authorities increasingly look to China for significant investments in the country, particularly its stagnant minerals sector. In 2015, General Nice, a Hong Kong mining firm, announced plans to develop a $2 billion iron ore mine, while in September 2016, Shenghe Resources purchased a stake in Greenland Minerals and Energy, seeking to develop rare earth minerals. These investments—although not yet fully realized—can boost Beijing’s status as a preferred economic provider in Greenland, minimizing both the Danish and U.S. position. This perception was further amplified by a 2014 decision by the U.S. Air Force to award the Thule base maintenance contract to Exelis Services, a Danish subsidiary of U.S. company Vectrus, which was a large blow to the Greenlandic economy (Greenland co-owns the company that previously held the contract). Denmark and Greenland argue that Exelis is only a shell company and therefore not eligible to win the contract, which can only be awarded to a Danish-Greenlandic company according to the existing defense agreement. The three countries continue to negotiate to find a solution to the issue.

Against this backdrop, Greenland’s parties approach independence, its relationship with Copenhagen and Washington, as well as with Beijing, differently. Mr. Kielsen’s nationalist Siumut (Forward) party has historically been a force for independence, although he personally represents its moderate wing, and he has been hesitant to issue public demands to Copenhagen and Washington. He faces challenges from both sides of the political spectrum. From the left, Inuit Ataqatigiit (the Community of Inuits) or IA, a more pro-Danish, Green party that has traditionally been Siumut’s main challenger, seeks the premiership. Siumut and IA have governed together in a grand coalition since 2016, and the IA leadership shares Mr. Kielsen’s pragmatism when it comes to the relationship with Denmark and the United States. Consequently, an IA victory is unlikely to have major foreign policy implications.

From the right, several minor, radical nationalist parties try to paint Mr. Kielsen as a Danish puppet who has failed to push Greenland’s advantages vis-à-vis Denmark and the United States. The big unknown is the recently formed Nunatta Qitornai (the Descendants of Our Land) party, led by Vittus Qujaukitsoq, a former foreign minister who left Siumutafter a failed leadership challenge last year. The bullish Mr. Qujaukitsoq blames many of Greenland’s problems on Denmark and the United States. As foreign minister, he filed an official complaint with the UN Human Rights Council over Denmark’s treatment of the Inuit regarding issues related to the U.S. military presence. Mr. Qujaukitsoq has threatened to terminate Denmark and the United States’ presence on Greenland. Unfortunately, there are no reliable opinion polls to judge the strength of Nunatta Qitornai, but the timing of the snap election is particularly challenging, as the party has yet to fulfill the requirements necessary to be on the ballot. […]