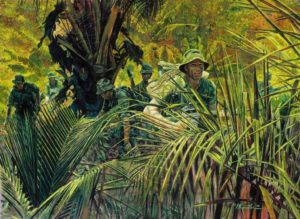

On May 13, 1968, 12,234 Army National Guardsmen in 20 units from 17 states were mobilized for service during the Vietnam War. Eight units deployed to Vietnam and over 7,000 Army Guardsmen served in the war zone. Company D (Ranger), 151st Infantry, Indiana Army National Guard arrived in Vietnam in December 1968.

Gilbert T. Seawall takes TAC readers back to the days following Martin Luther King Jr.s assassination in Memphis and the Berkeley California turmoil.

Dividing U.S. politics and culture into old and new, 1968 remains a landmark year in the public mind. Amid failure in Vietnam, the much-detested President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not seek re-election in late March, and four days later, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Cities across the country burned.

Berkeley, where I lived, was in turmoil. News magazines and television specials—obsessed with the California youth revolt, psychedelia, and free sex—depicted Berkeley as a red-hot center of radical politics and rapture. Street people and malcontents were pouring into town, looking for thrills and drugs. Then that night, horribly, Robert F. Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. I was minutes from Good Samaritan Hospital the next day seeing a draft lawyer when Kennedy died.

During the ill-starred Democratic National Convention and Chicago riots from August 26 to 29, antiwar protesters shouted at police and news cameras, “The whole world is watching!” They knew which side most Berkeley, Wisconsin, and Harvard students would take. Working-class America, facing a harder nut, did not join the rage or rapture. Condemned as lowbrow and backward, the butt of educated contempt, they turned instead to Alabama’s former governor George Wallace for political relief.

The prevailing campus spirit at Berkeley in the mid-Sixties had been Camelot-style liberal, venerating the fallen hero JFK.

Then, quite suddenly, cool moved from Kennedy-style white Oxford shirts and can-do pragmatism to longhaired forest creatures quoting Kahlil Gibran. Sorority girls wearing madras skirts donned Mexican peasant blouses one day and dangly silver earrings the next. Accessories included funky Volkswagen buses.

By 1968, fueled by psychedelics—”Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”—a small, visible, largely coastal beau monde grew stylishly clubby. In Laurel Canyon, the Los Angeles music and drug scene was already getting very dark. Entrepreneurs like Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner and poet Rod McKuen—as well as account executives on Sunset Strip and Madison Avenue—realized there was big money to be made in the counterculture.

While Timothy Leary’s bliss-seekers chanted tune in, turn on, and drop out in Wheeler Auditorium, Marxist visionaries plotted the end of police state Amerika.

From the early Peter, Paul, and Mary and Kingston Trio to Bob Dylan and Jefferson Airplane, social redemption and brotherhood had arrived on 33-rpm vinyl in pretty tunes and words.

What was beginning to take shape during the August 1968 Chicago demonstrations was a McLuhanesque struggle for political mastery that has never ended.

Fifty years later, California Senator Kamala Harris, born in 1964, tweets, “We won’t be silent about race. We won’t be silent about sexual orientation. We won’t be silent about immigrant’s rights. These are the very issues that define our identity as Americans.” The “whys” of a Purple Heart and American commonwealth do not cross her mind.

Harris’s stagey exclamations have a direct line to a liberation movement that is a half-century old, but with a difference. Politicos trying for selfish ends to strip “white culture” of whatever legitimacy it still possesses are saddled to technocracy. Twitter-based politics and Silicon Valley’s electronic netherworld perfecting mind control? No problem.

Read more here.

If you’re willing to fight for Main Street America, click here to sign up for my free weekly email.